From Passwords → OTPs → Passkeys → (and the Rise of OPAQUE)

User authentication is essential for every digital product, but it is also the most outdated part of the mobile stack. Most systems still rely on the same idea we got from the early days of the web:

"Give me a secret, and I'll check if it matches mine."

This model of passwords, OTPs, and shared secrets has been the standard for the past twenty years.

It's also the source of almost every major authentication breach in the last 20 years. But the world has changed. Today, smartphones act as hardware cryptographic devices with secure enclaves, biometric sensors, and encrypted key storage. Modern authentication should not rely on memorized strings. Instead, it should use the hardware that everyone already carries.

We are now entering the first true evolution of authentication in decades:

We are moving from using secrets to using cryptographic proof, thanks to passkeys and new password protocols like OPAQUE.

This article covers:

- The four generations of mobile authentication

- A preview of OPAQUE

- A deep technical dive into passkeys

- A full breakdown of the registration and authentication lifecycle

- Pitfalls to avoid and how to test passkeys correctly

Let's begin with the basics.

1. The Four Generations of Mobile Authentication

Most mobile authentication today falls into four categories:

i. Password-Based Authentication (Legacy Era)

Users enter a username and a password. The server stores a salted hash. This is still the most common method, but it is fundamentally insecure:

- Users reuse passwords

- Databases leak

- Credential-stuffing attacks work

- Phishing still succeeds

- Mobile users often paste passwords from insecure managers.

ii. OTP-Based Authentication (Layered Secrets)

To "strengthen" passwords, apps added: Email OTP, SMS OTP, TOTP (Google Authenticator), Push approvals.

These steps add friction but do not fix the main weakness: You are still passing secrets around.

OTPs can be: Hijacked, Intercepted, SIM-swapped, Phished, Replayed.

iii. Token-Based Authentication

- OAuth / OpenID Connect

- Magic links

- JWT sessions

- Hardware keys (YubiKey, smartcards)

This is a big improvement for user experience and security, but it still depends on users getting and sending a token.

iv. Cryptographic Authentication (Modern Era)

This marks a major change in how authentication works:

- Passkeys (WebAuthn + FIDO2)

- OPAQUE (modern password protocol)

- Device-bound cryptographic keys

- Hardware-backed authentication flows

In this approach, no secret is ever sent over the network. Authentication is now based on cryptographic proof instead of comparing strings.

This is where mobile authentication has arrived.

2. OPAQUE (Preview): Modern Passwords Without Password Risks

Passwords will not go away overnight, especially for enterprises, regulated businesses, or older systems. This is where OPAQUE becomes important. OPAQUE is a next-generation password protocol that fixes the most dangerous flaw in password systems:

The password is never revealed to the server, and the server stores nothing that could be used to recover it. OPAQUE eliminates offline cracking, database hash leaks, and credential replay.

A detailed look at OPAQUE will be covered in another article. To see where mobile authentication is headed, we need to look at passkeys.

3. Passkeys: The Deep Mobile Technical Overview

Passkeys use asymmetric cryptography stored in a smartphone's secure hardware instead of passwords.

A passkey =

- A private key stored in Secure Enclave (iOS) or StrongBox/TEE (Android)

- A public key stored in your backend

- A credentialId identifying the keypair

- A set of metadata describing the authenticator

During login, the device:

- Uses biometrics to unlock the private key

- Signs a challenge from the server

- Returns the signature

- Server verifies using the stored public key.

No password. No OTP. No shared secrets. No phishing. Passkeys are not just a user experience improvement. They are a completely new way to handle authentication.

4. Passkey Terminology

To design or troubleshoot passkeys, you must understand the cryptographic components.

Credential ID (credentialId)

- Random, opaque identifier generated by authenticator

- Points to the private key in secure hardware

- Stored on the backend

- Not a secret

Public Key (publicKey)

Used by your backend to verify signatures.

Stored server-side. Usually ES256 (ECDSA P-256 + SHA-256).

Other algorithms

- ES256 → -7

- RS256 → -257

- EdDSA → -8

Challenge

Random bytes (32+ bytes), Base64URL-encoded. Generated per request and used to prevent replays.

RP ID

The domain that credentials bind to. Passkeys cannot be used across RPs.

User Handle

Internal stable user identifier (bytes). Used to auto-select the correct credential.

clientDataJSON

Contains:

- challenge

- origin

- type (webauthn.create / webauthn.get)

Signed as part of the request → prevents phishing.

authenticatorData

Binary block containing:

(a). RP ID Hash (32 bytes) A SHA-256 hash of the RP ID (e.g., SHA256("yourapp.com")).

Purpose:

- Ensures the credential is used only for your domain

- Prevents cross-domain replay

- Provides built-in phishing resistance

If this hash doesn't match your domain → reject.

(b). Flags (1 byte) (UP, UV, AT): A bit-packed field indicating what happened during authentication.

UP — User Presence (bit 0)

User physically interacted (tap, click, biometric prompt visible).

Must be true for all valid authentications.

UV — User Verification (bit 2)

User was verified via biometrics or PIN (Face ID, Touch ID, Android Biometrics).

Confirms who is present, not just that someone is present.

Recommended for sensitive apps.

AT — Attestation (bit 6)

Indicates attestation data is included (registration only).

Used to confirm the hardware type (e.g., Secure Enclave, YubiKey).

Most consumer apps ignore this for privacy and simplicity.

(c). signCount (4 bytes)

A counter maintained by the authenticator.

- Normally, it increases with each authentication.

- Some devices always return 0 (synced passkeys, some Android authenticators)

Purpose: detect cloned credentials or malicious replays.

Interpretation:

- new > old → normal

- new == old → acceptable for devices that don't increment

- new < old → suspicious; potential cloning

Never fail repeated 0 values—they're normal for many synced passkey systems.

4. Optional Attestation Data (Registration Only)

Includes public key, AAGUID, and attestation statement.

Used to verify authenticator hardware identity.

Typically required only in enterprise/high-assurance environments.

signCount

Monotonically increasing value.

Detects device cloning or replay attacks.

5. The Passkey Lifecycle

Passkeys operate through two main cryptographic steps:

- Registration (Credential Creation)

- Authentication (Assertion / Login)

Both require precise server-side verification.

5.1 Registration — Creating a Passkey

The goal:

Create a keypair and link it to the user and the RP ID.

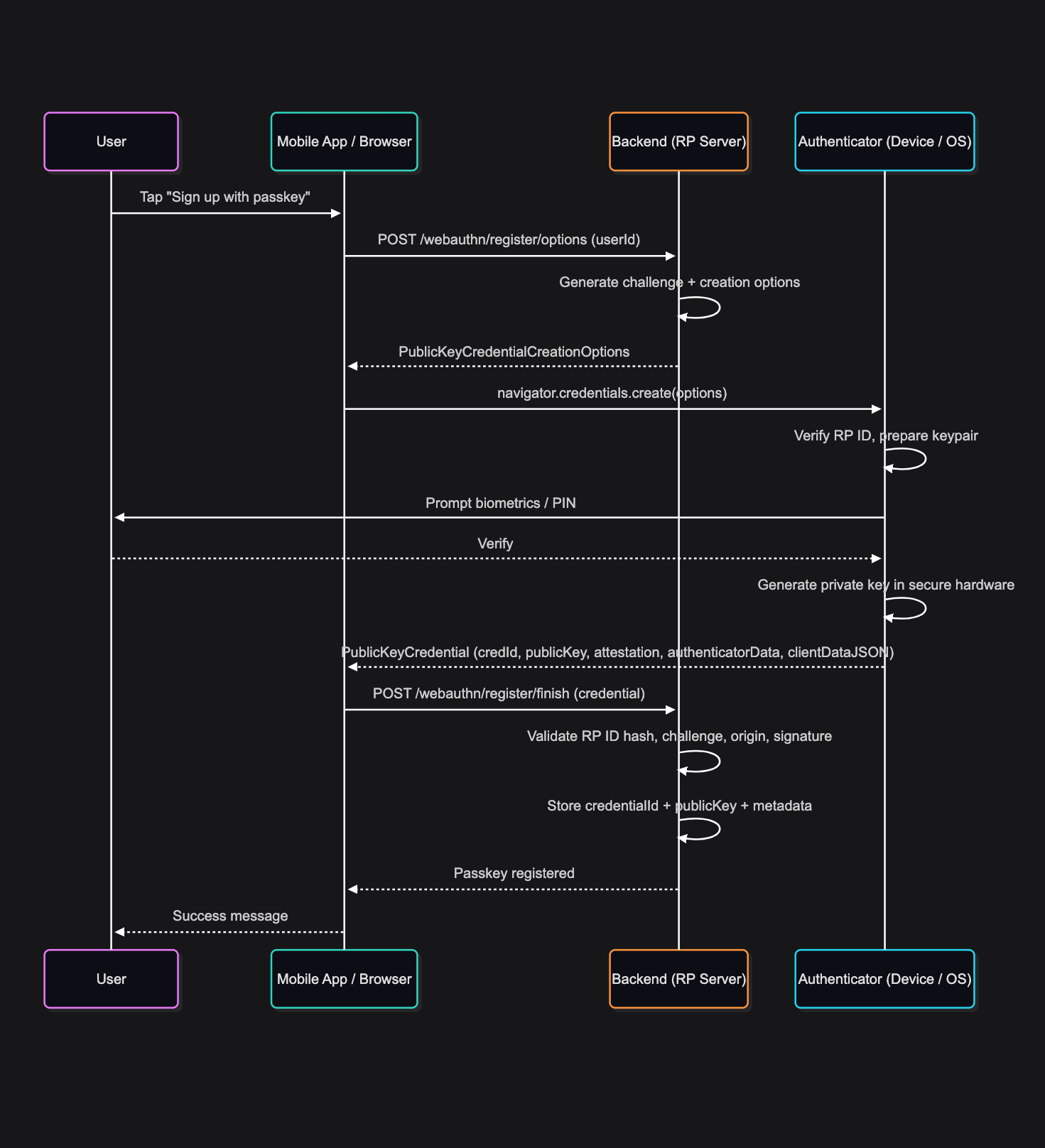

Registration Sequence Diagram

What the backend must check

- Challenge matches the original

- clientDataJSON.origin matches RP origin

- RP ID hash matches your domain.

- Signature validates using the returned public key

- Attestation (if used) is trusted.

- signCount captured

Common mistakes during registration

- ❌ Incorrect RP ID — passkey will never authenticate later

- ❌ Bad Base64URL encoding — server cannot match credentialId

- ❌ Weak or reused challenges

- ❌ Not verifying clientDataJSON.origin

- ❌ Strict attestation failures (for no reason)

- ❌ Storing credentialId incorrectly (common bug)

How to test registration

- End-to-end test on real iOS and Android devices

- Test duplicate registrations for same user

- Replay the registration response (should fail)

- Validate that credentialId lookup is exact (no encoding issues)

5.2 Authentication

The goal is: Prove possession of the private key.

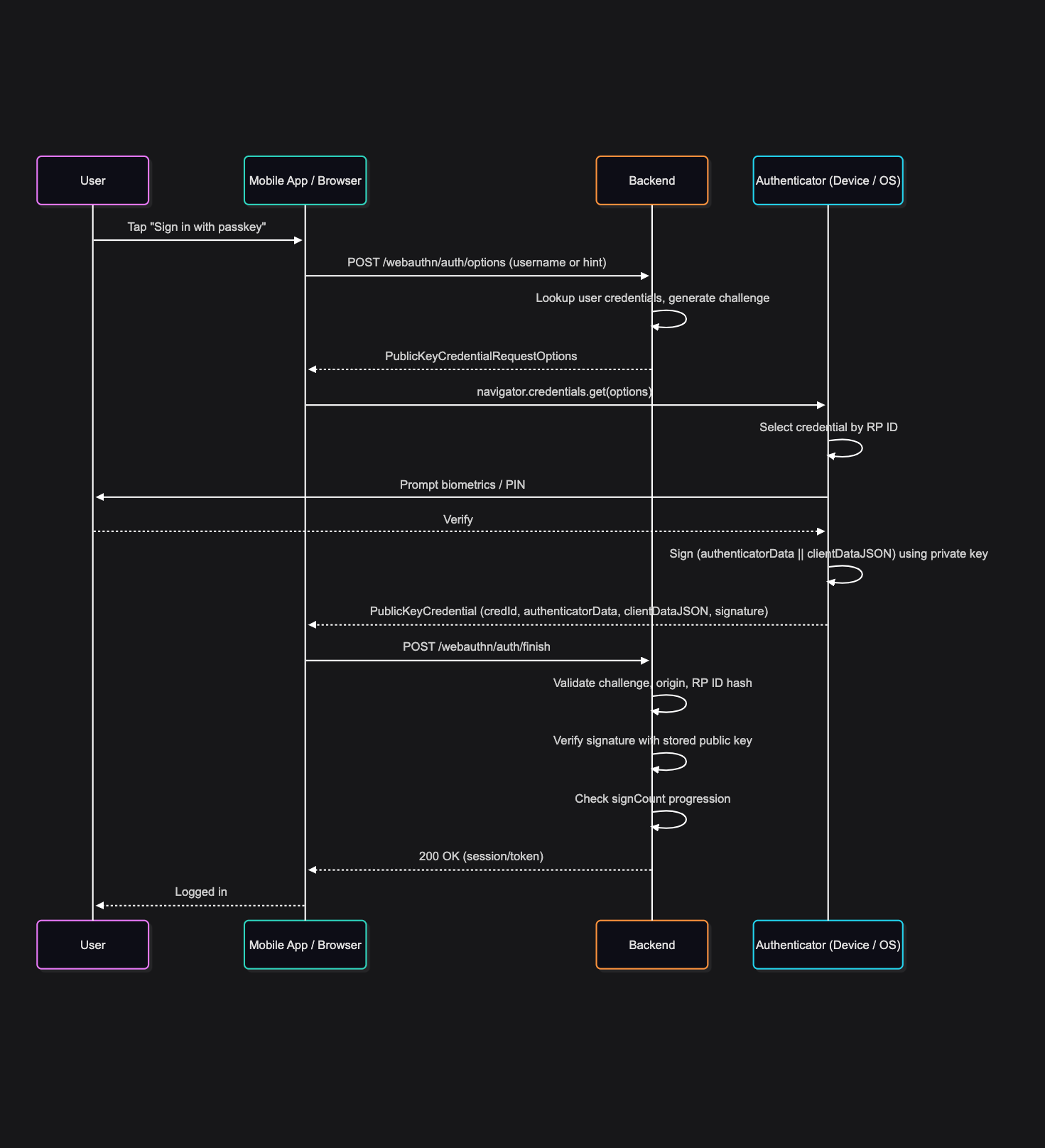

Authentication Sequence Diagram

What the backend must check

- Challenge matches issued a challenge

- RP ID hash matches the expected RP.

- clientDataJSON.origin is allowed

- Signature is valid

- Flags:

- UP (user presence) required

- UV (user verification) is strongly recommended.

- signCount >= previous signCount

Common mistakes during authentication

- ❌ Failing to check origin → phishing vulnerability

- ❌ Ignoring RP ID hash → credentials could be misused by rogue domains

- ❌ Not enforcing signCount progression → clone attacks go undetected

- ❌ Using the wrong public key for verification

- ❌ Treating credentialId as proof of identity

- ❌ Weak session issuance after authentication

How to test authentication

- Authenticate several times to check the signCount increments.

- Authenticate from multiple devices with separate passkeys.

- Replay an old assertion (should fail due to mismatched challenge)

- Modify clientDataJSON (should fail)

- Use invalid credentialId (should reject)

- Verify cross-device passkey flows (iOS → macOS → Android)

6. Device-Bound vs Synced Passkeys

Passkeys can work in two ways:

Device-Bound

- The private key never leaves the secure hardware.

- Maximum security

- Good for enterprise, regulated apps

Synced

- Private key is stored in encrypted form in:

- iCloud Keychain (Apple)

- Google Password Manager (Android)

- Provides cross-device access

- Still end-to-end encrypted

- Still not accessible to platform vendors

Both options are much more secure than using passwords and OTPs.

| Factor | Password | OTP | Passkey |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phishing | High | Medium | Zero |

| DB Breach Impact | Catastrophic | Medium | Harmless |

| SIM Swap | N/A | High | N/A |

| UX | Poor | Medium | Excellent |

| Cryptography | Weak | Weak | Strong |

| Biometrics | Optional | Bad | Native |

| Cross-Device | Manual | Manual | Automatic |

Passkeys offer a unique mix of security, speed, privacy, and ease of use.

8. Architectural Considerations for Mobile Passkey Support

To run in production, a system needs:

Credential Store

- credential_id

- public_key

- algorithm

- sign_count

- authenticator type

- user_id

Challenge System

- cryptographically secure

- short-lived

- one-time-use

WebAuthn Server Verification

- clientDataJSON + authenticatorData parsing

- RP ID hash check

- signature validation

- signCount progression

Multi-Key Support

A single user can have many passkeys on different devices.

Revocation Mechanisms

Users should be able to:

- remove passkeys

- reset credentials

- Add device-bound keys

Conclusion

Mobile authentication is being redesigned from the ground up. We are moving away from shared secrets and weak OTP flows to hardware-backed cryptographic authentication, which removes many types of vulnerabilities.

Passkeys are the biggest step forward in authentication since OAuth was introduced.

They make authentication:

- Unphishable

- Frictionless

- Cryptographically secure

- Hardware-enforced

- Cross-device seamless

OPAQUE will update password-based systems, but passkeys are setting a new standard for mobile identity.

Follow-up posts will cover:

- How to: Integrating passkeys on iOS (Swift)

- How to: Integrating passkeys on Android (Kotlin + Credential Manager)

- OPAQUE: The future of password security

Bonus:

If you're working in authentication or security engineering, you can test your passkeys for free here: https://webauthn.io/